exploring italy's cultural treasures

The Story of Saint Mark's Basilica

It's written all over its face.

Shelli Lott

10/30/20255 min read

It pays to ponder the details, especially when you travel. Because details often tell stories.

The story of Saint Mark's Basilica is told in the mosaics over four of its doorways. If you're facing the basilica, the story reads 'backward,' from right to left. The mosaics tell the story of the translatio of the body of Saint Mark. What is a translatio? Think of it this way: A pilgrimage is when people travel to visit a relic. A translatio is when a relic travels to the people.

In most cases, when an important relic was "translated," it looked a lot like theft. But, the belief back then was that a relic would only allow itself to be relocated, or translated, if the relic's saint wanted it to be relocated.

Saint Mark, the basilica's namesake and patron saint of Venice, was a disciple of saints Peter and Paul. He was also one of the Four Evangelists, or gospel writers. So he was a very important saint.

To "read" the story of the translation/theft of Mark's body, we need to begin in front of the portal on the far right of the facade. In the year 828, two Venetian merchants went to Alexandria, Egypt, and stole the body of Saint Mark.

Far right portal mosaic: Theft of the Body of Saint Mark

Alexandria is where Mark was likely martyred and buried. He was believed to have been the apostolic missionary to the Northern Adriatic, so the Venetians probably regarded him as one of their own.

Although Alexandria had been an important city in early Christianity, by the 9th century, it was under Muslim control. Supposedly, the two Venetian merchants heard that the Muslims were going to desecrate or destroy the place where the body of Mark was kept -- possibly to repurpose the location for Muslim practices -- not beyond the realm of possibility.

So the two Venetians, with the help of a priest, took the body. According to some sources, they just happened to have the body of Saint Claudia with them and put her body in its place. Then they hightailed it back to their ship with Mark's body.

Theft of the Body of St. Mark, by Jacopo Tintoretto, c. 1562-66

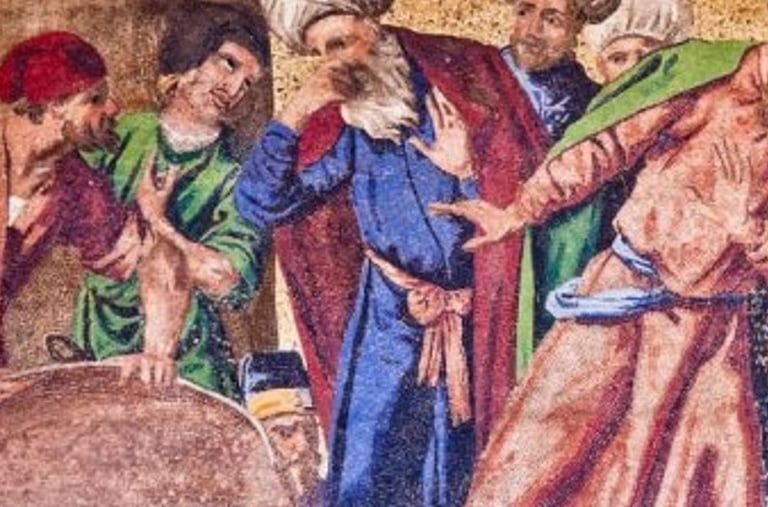

After the Venetian merchants had boarded their ship with the body, the Muslim customs officials demanded to search the vessel. However, the wily Venetians had hidden the body in a basket of cabbage and pork. The Muslim officials, forbidden to touch pork, were repelled by it and the body was safe.

The customs official holds his nose as one of the Venetians seems to say, "Trust me. There's nothing to see here but pork."

This first mosaic is not very old by Venetian standards. It was created in the 1600s.

Detail of far right portal mosaic: Theft of the Body of Saint Mark

Now we move one portal to the left, to the second mosaic.

So the Venetians safely "translated" the body to Venice, where immediately plans were made for a great basilica to house the relics of St. Mark. Construction began in 829.

This mosaic also dates from the 1600s. It shows the arrival of the body of Saint Mark to Venice.

Second portal mosaic: Arrival of the Body of Saint Mark

In this second mosaic, the body of Saint Mark isn't really visible. But, you may have noticed that several of the people in the scene are looking up.

On the voyage, they wrapped Mark's body in a sail and hoisted it up the mast to keep it safe and hidden. So that's where Saint Mark is in this image -- rolled up in the sail.

Next, moving to the portal left of the main central doorway, we come to the third part of the story. This mosaic is the newest of the four Translatio mosaics, dating from the 1700s. Stylistically, it's quite different from the others and has the feel of a painting, with perspective, foreshortening, and more realistic-looking figures.

Third portal mosaic: Veneration and Welcome of the Body of Saint Mark

Mark was given a warm welcome upon arrival in Venice. This mosaic shows the Doge, Dogaressa, and members of the Signoria (Venetian senate), along with members of the clergy, paying homage to the relic.

Moving on, at the far left of the basilica's facade is the final portal with the last mosaic in the Translatio series. This fourth mosaic is the oldest of the exterior mosaics and the only one that is original to the basilica. It dates from around 1260-70, so it's quite older than the others, which have replaced earlier originals.

Fourth portal mosaic: The Translatio of the Body of Saint Mark.

This is also the oldest known contemporary depiction of the basilica, which was constructed around 1060. The mosaic gives us a good idea of what the basilica looked like in the 1200s, when the mosaic was created. In fact, it looked very much like it looks today. The mosaic shows the four horses (the Quadriga) already in their place, and the domes which had been heightened from the original 1060 design.

It's above the doorway known as the Porta Sant'Alipio. If you're fortunate to see this in person, take a moment to notice the other old and precious things in front of you: The rare and beautiful varieties of marble in the columns, the four symbols of the Evangelists against the turquoise blue background, and the decorative grillwork.